Sarah Baartman was a South African lady who was popular for having large buttocks that became an attraction to Europeans around the early 1800s. She was called Saartje or Saartjie, a diminutive form of Sarah and it is unclear if it had another meaning.

The biography of Sarah Baartman will make you understand why her story is so important. Considering that she had died young – around the age of 25 or 26 – Sarah Baartman remains a symbol for many important social issues.

Before we delve into details about her, let us summarise 10 facts about Sarah Baartman that you should know.

10 facts about Sarah Baartman

- Sarah Baartman was born in 1789 and was a Khoisan descendant from South Africa. She was one of the most historically important female black figures in recent times despite dying at a young age of 26.

- She had a daughter named Okurra Reaux after her French owner, Mr Reaux, raped and impregnated her as an experiment. Her daughter died of an unknown illness when she was only five years old.

- One of her most popular nicknames was the “Hottentot Venus”, a nickname that has been used to describe other women exhibited for their perceived sexual appeal.

- Baartman spoke to a passable level three different languages besides her native language to a passable level. These were English, Dutch and French.

- Sarah Baartman allegedly had two other children who died in their infancy.

- While she was exhibited in England, it raised many issues concerning slavery and the African Association and Zachary Macaulay had to step in.

- Reports claim that Baartman was baptised at Manchester Cathedral and that she got married on the same day.

- When she moved to France, she was sold by Henry Taylor to S. Reaux, who was an animal trainer and there are accounts that claim that he put a collar around her neck.

- Even after her death in 1815, her skeleton and her body cast were put on display in Muséum d’histoire naturelle d’Angers, Angers, France for over 60 years. They were removed in 1874 and 1876 respectively.

- Nelson Mandela, as the president of South Africa, wrote to French authorities to get them to allow her remains to be returned to her homeland for a proper burial.

Also read: Ini Edo Biography: Early Life, career, awards, marriage, net worth & more

Sarah Baartman Biography: Early Life

Sarah Baartman was born as Saarjtie (a diminutive form of Sarah) in 1789 in South Africa in a colony known as The Cape of Good Hope. Not long after her birth, supposedly when she was at the age of one, her family moved to Gamtoos Valley, an Eastern Cape Province in South Africa that was named after the Gamtoos River.

Baartman was born into a Khoikhoi family and they are known as pastoral people who engaged in nomadic activities. In fact, her father was alleged to have died at the hands of Bushmen while he drove cattle.

Likely, Sarah Baartman had a local birth name but there is no information on this. She grew up among her people and with her mother who later died before she left South Africa. Also, there was a mention of her keeping a tortoise-shell necklace until her death in France. This necklace was a part of an old puberty rite of passage where a girl’s female family member gives her a necklace such as that, which Sarah Baartman kept.

Around the 1790s, she moved to Cape after one Peter Cesars encouraged her to do so. Peter Cesars was a free black man; a person from an enslaved ancestor who was not a slave. Also, as a Khoisan, Baartman could not be formally branded and owned as a slave. So, she worked for Hendrik Cesars, Peter’s brother as a wet-nurse after working as a washerwoman and nursemaid for Peter Cesars for about two years.

There is some evidence in various stories told about her that she probably had two children during this time but that they died in their infancy. She was also reportedly in a relationship with a Dutch soldier named, Hendrik Van Jong. The relationship was said to have ended when the soldier’s regiment left Cape.

When a certain Scottish military surgeon, William Dunlop, entered the picture, Sarah Baartman’s life changed. Many reported accounts mentioned that Dunlop was the first person that saw her as potential as a showpiece. This was likely because he already had exhibition knowledge at the time by supplying exotic animal specimens to British showmen.

The surgeon approached her several times and asked her to go to Britain to exhibit herself and after her initial refusal, she agreed to go only if Hendrik Cesars went along. Cesars too initially disagreed but later changed his mind likely because he had gone into debt and saw it as an opportunity to make some fortune.

The governor of Cape at the time, Lord Caledon, also later said that he regretted giving permission for the trip after learning its true purpose. This was revealed in an affidavit that the alleged owner of a museum in Liverpool, Mr Bullock, provided to the Court of King’s Bench.

The affidavit, dated 26th November 1810, mentioned that Dunlop had claimed to have “a female Hottentot” on the way from the Cape of Good Hope that “would make the fortune of any person who shewed her in London.” Hottentot is described as an offensive way of referring to a Khoikhoi person.

Sarah Baartman Britain Exhibition

In 1810, Hendrik Cesars and Alexander Dunlop brought Sarah Baartman to London and they lived in what was regarded as the most expensive part of London then – Duke Street, St. James. The first time the pair exhibited her, it was in the Egyptian Hall of Piccadilly Circus on 24 November 1810.

According to a Wikipedia account, Cesars acted as the showman in that instance. Also, it is important to note that freak shows were already gaining popularity in England since as early as the 16th century according to an article titled Freak show.

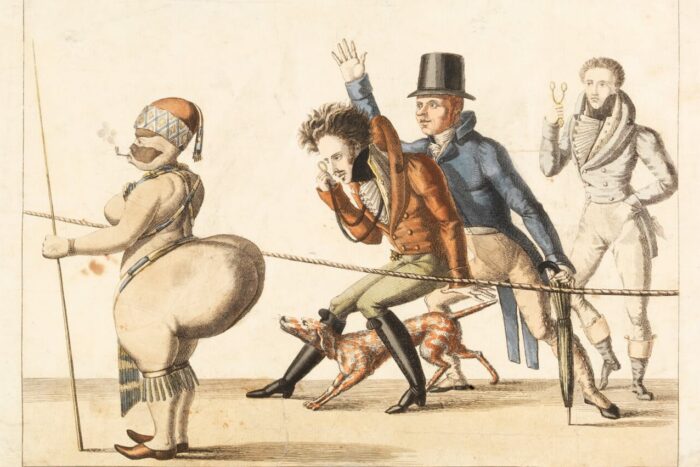

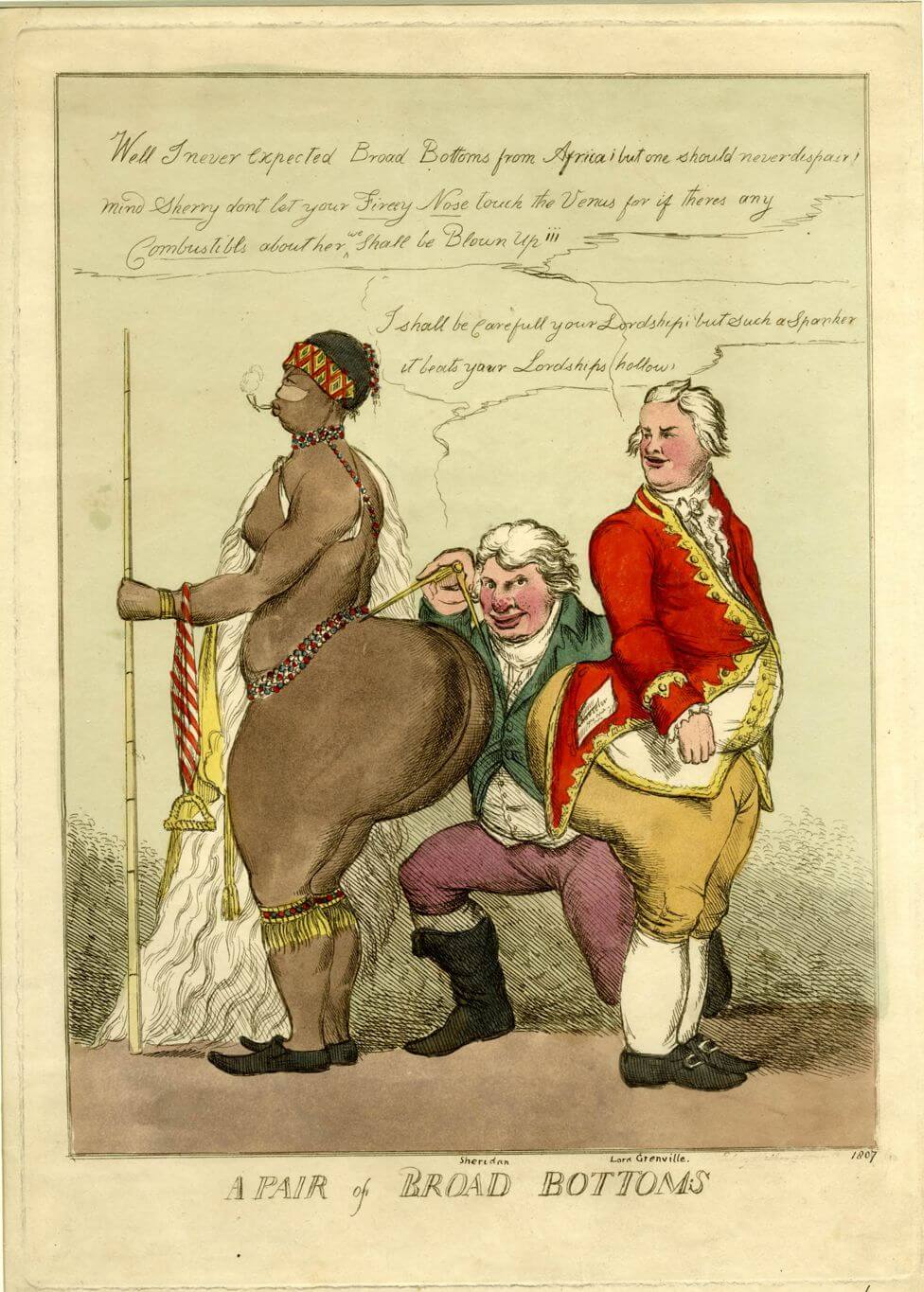

Therefore, the main purpose of displaying Baartman was because of her unusually large buttocks, which to the British was very strange. Thus, Dunlop and Cesars hoped to draw a crowd willing to see Sarah or Sarjtie Baartman as a ‘freak of nature’ and not a usual person. Meanwhile, there were several accounts that agree that she never consented to be displayed nude and always had clothing pieces to cover her genitalia.

However, not long after her exhibition began in England, it also stirred up unrest and scandals. One of the reasons was that the Slave Trade Act 1807 had just been passed a few years past. This was an Act of the Parliament of the United Kingdom prohibiting the slave trade in the British Empire. Although it did not abolish the practice of slavery, it did encourage British action to press other nation-states to abolish their own slave trades.

Another reason was that there was reportedly violence involved during her exhibitions (we could not find a description of what the violent acts were and on whom they were performed).

These two reasons gave birth to protests led by Zachary Macaulay, a popular Scottish statistician who was an antislavery activist. It resulted in court cases where a society called the African Association, protested that Sarah Baartman was living under degrading conditions and that she was being coerced.

In the end, the court case did not amount to much because Sarah Baartman herself allegedly confirmed the following:

- That she had come to London on her own free will and had not been forcefully brought or tricked.

- That she was not under restraint (not treated as a ‘property’) and had not been sexually abused.

Following the court cases, her popularity grew and so did her value as a spectacle for exhibitions. Before leaving England, after touring other parts asides London, she reportedly got married and was baptised at Manchester Cathedral on the same day. But, there was no mention of who her husband was.

Cesars eventually left the business and Dunlop continued to display her until he died in 1814.

France exhibition and subjugation

Sarah Baartman fell into the hands of one Henry Taylor who took her to France in September 1814. When they got there he sold her to S. Reaux, who was an animal trainer. This man was described as not being as decent as Dunlop and Cesars and he made her exhibit under more “pressured conditions”.

Her ordeal lasted all of 15 months and they were usually at the Palais Royal, and she was more for science inclined audiences than the public curiosity. There is a general consensus that she was without a doubt enslaved in Paris, France. There was no such thing as the Slavery Act that existed in England and the scientific crowd did not have to worry about slavery protests.

Yet, she was still able to maintain that she did not want to be seen nude. Even when they offered her money, Sarah Baartman only agreed to undress to the extent that her genitalia was hidden by some piece of clothing. There were many paintings of her that were made for scientific and ‘research’ purposes.

One notable racial discrimination and scientific racism that she endured was people’s curiosity about whether she had elongated labia. This was because, by the 18th century, there was already an obscene interest among Europeans that the Khoikhoi females usually developed elongated labia minora.

Another thing that made her interesting, especially to Georges Cuvier, founder and professor of comparative anatomy at the Museum of Natural History, was that he thought she would provide him with proof of a so-called missing link between animals and human beings. S. Reaux also raped and impregnated her as an experiment. The child’s name was Okurra Reaux, and she died at the age of five of an unknown ailment.

According to two researchers, Clifton Crais and Pamela Scully, who wrote a research work on Sarah Baartman, they described her life in Paris in one touching paragraph. They wrote:

“By the time she got to Paris, her existence was really quite miserable and extraordinarily poor. Sara was literally [sic] treated like an animal. There is some evidence to suggest that at one point a collar was placed around her neck.”

Sarah Baartman’s death

Just over a year after she went to France, Sarah Baartman died on 29th December 1815. She died around the age of 26 of a certain inflammatory disease that could have been either smallpox, syphilis or pneumonia. Also, while a scientist named Georges Cuvier had dissected her body, he didn’t conduct an autopsy to ascertain what had killed her.

Cuvier had met Sarah Baartman while she was alive and while he studied her, he confirmed that she was quite intelligent. Besides speaking her native tongue, she could speak Dutch, some English and had an understanding of French. He also wrote that she was lively but he likened it to the “quickness of a monkey”, showing his racial prejudice.

Her death did not stop the interest in her body. Up until 1976, there was a body cast of Sarah Baartman in Muséum D’Histoire Naturelle d’Angers, Angers. It stood beside her skeleton which the museum had retained. But, other events would see this further subjugation of Sarah Baartman taken down.

Sarah Baartman’s legacy

While since the 1940s, there have been calls for her remains to be returned to her country, it took many more years before this was actualised. First, complaints and protests in France forced the museum to take down her body cast in 1976. The body cast had an emphasised portrayal of her large buttocks or steatopygia, an accumulation of fat on the buttocks. The museum had removed her skeleton from display in 1974 after people said it was a degrading representation of women.

Diana Ferrus, a writer of Khoisan descent, wrote a poem in 1978 about Sarah Baartman titled “I’ve come to take you home”. The poem raised more awareness of Sarah, furthering her popularity.

Stephen Jay Gould, a scientist and researcher also wrote about her in his book, The Mismeasure of Man in 1981. The book discusses how IQ cannot be determined by a person’s race.

It was not until 1994 after Nelson Mandela wrote to France formally, in his capacity as the President of South Africa, that the country paid heed. It took eight years of arguments and legal debates before France agreed on 6th March 2002 to return Sarah Baartman’s remains.

Her remains entered Gamtoos Valley on 6th May 2002 and she was buried on 9th August 2002 on Vergaderingskop, a hill in Hankey, Eastern Cape, South Africa.

Reports show that there have been many more Khoikhoi people who were taken from there homelands and displayed as attractions in Europe, however, Sarah Baartman was the most popular of them. Also, there were arguments that most of the drawings depicting her may have exaggerated the size of her buttocks for public entertainment.

Also, it was from her exhibition around Europe that many racist views of African women as “savage women” distinct from “civilized female” sprung.

Furthermore, Sarah Baartman’s story has inspired many works in the media. There are also several published articles, essays, research works, books, art pieces, and so on about her. Some examples of such works are provided in the section on popular works inspired by Sarah Baartman.

She is a hot topic among feminists, Africans and human rights activists. A recent example is when Nigerian singer Dice Ailes, in October 2019, used a caricature of her in the art cover of his song “Ginika”. Following the social media outrage it generated, the artist came forward to clear the air and to state that he knew who Sarah Baartman was and that he wanted more people to talk about her. Thus, he was using his song to “celebrate” her.

Listen to Dice Ailes’ song Ginika here:

[embedyt] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CAaN6LZZ5wk[/embedyt]

Final Thoughts …

While many have come to symbolise Sarah Baartman as a symbol of injustice against women at the hands of men and prejudicial treatment of blacks by whites, it is important to remember her as a woman who once lived. Despite being a ‘free woman’ all her life, at least legally, she was unable to escape the shackles that her biology and race placed on her feet.

Remarkably, after two centuries, she is now getting the kind of legacy she deserves. Her sojourn in Europe is widely known and respected. It has led to many radical discussions and changes both in Africa and the world at large. These discussions and changes are evident in the way people now speak about race and gender.

10 popular works inspired by Sarah Baartman

- One of the earliest is a pantomime titled The Hottentot Venus that was featured at the New Theatre, London on 10th January 1811.

- Elizabeth Alexander, an American writer, talks about her story in a 1987 poem and 1990 book, both were called The Venus Hottentot.

- Lyle Ashton Harris and a model, Renee Valerie Cox created a photographic image, Hottentot Venus 2000.

- There was a 2010 movie titled Black Venus, which was directed by Abdellatif Kechiche and starred Yahima Torres as Sarah.

- Hendrik Hofmeyr composed a 20-minute opera titled Saartjie, which was to be premiered by Cape Town Opera in November 2010.

- Jay-Z’s “The story of O.J” has a part that features Baartman as a cartoon caricature.

- Nitty Scott makes reference to her in her song titled “For Sarah Baartman“.

- Sarah Baartman Hall, University of Cape Town, renamed Memorial Hall on 8th December 2018.

- Zodwa Nyoni debuted a new play called A Khoisan Woman – a play about the Hottentot Venus at Summerhall in 2019.

- Royce 5’9 references Sarah Baartman in his song “Upside Down” in 2020.